Is Europe facing a slow and agonising decline?

Draghi's report concludes that Europe has reached the point where, without action, we will have to either compromise our welfare, our environment or our freedom.

Slowing growth, productivity problems, a lack of innovation, an ageing population and over regulation are the stuff of nightmares for any country or continent that wants to become rich, or stay rich. This was the big news story of last week, and understandably, many of us didn’t want to hear it. Mario Draghi's long-awaited report, "The future of European competitiveness", has diagnosed its ailing patient, and it calls for drastic lifestyle changes if a long-term illness is to avoid becoming terminal. Unfortunately we will have to do considerably more than quitting smoking, taking more frequent exercise and eating a balanced diet (the French and Italians are exempted here).

If we fail to heed Dr Draghi’s advice, it will be a “slow agony” because “we have reached the point where, without action, we will have to either compromise our welfare, our environment or our freedom”.

These are the facts to support this statement:

We have a growth problem

Since 2002, real per capita disposable income in the US has grown almost twice as fast as in Europe. In other words, Europe was 17% behind the US in 2002 and the gap has now widened to 30%, while China has overtaken us.

We have a productivity problem

Workers in the US produced $73.7 an hour in 2019, France and Germany $69, and the UK a meagre $54.3. As the report cites: “The main reason EU productivity diverged from the US in the mid-1990s was Europe’s failure to capitalise on the first digital revolution led by the internet – both in terms of generating new tech companies and diffusing digital tech into the economy [...] if we exclude the tech sector, EU productivity growth over the past twenty years would be broadly at par with the US”.

We have a demographic problem

Compounding the productivity issue is the fact that the EU's labour force will shrink by 2 million workers a year until 2040. This means that we will need to rely even more on improving productivity to increase prosperity, or, if we were glass-half-full Americans looking at the situation, we might exclaim: “this is one helluva opportunity to increase workforce automation in the face of labour scarcity, yee ha, USA USA USA!”. Alas, in Europe we don’t gobble enough prescription drugs to ever get this enthusiastic.

We have an innovation problem

There is no EU company with a market cap of €100Bn or more that has been setup in the last 50 years. Not one. The USA, by comparison, has spawned six trillion dollar market cap companies (NVIDIA, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta), whilst Tesla is close. We also spend less on R&D and are much poorer at translating innovation into commercialisation.

We have an over-regulation problem

The EU’s regulatory stance towards tech companies hampers innovation, Draghi says, “[Europe] now has around 100 tech-focused laws and over 270 regulators active in digital networks across all member states.” Or to put it in very glib terms:

“The USA innovates, China replicates, the EU regulates”.

Is there such a thing as a European Dream?

If you want to make it big, you head to the USA. Hell, if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, isn’t that what Sinatra crooned as long ago as the 1950s? The European Dream, if there even is such a thing, aspires to a 40 hour working week, a month of annual leave and plenty of employment protection. Some would argue that this is a poor recipe for growth.

So is there a cure?

Yes, according to Draghi we should invest €800Bn (equivalent to 4.5 % of EU GDP) in a new industrial strategy for Europe. This injection of fresh funding, (a.k.a. debt) describes what the EU should do, but not the specifics and these come in four flavours. They all aim for growth, because growth is the panacea that lifts all boats, increases tax revenues to invest in public services etc. Draghi is not only an impressive thinker but a pragmatist, and his recommendations would unblock key areas where the EU is currently hamstrung:

Advancing the Capital Markets Union to provide better access to funds for startups, especially at later stages. Successful European companies eventually seek American or London based growth capital. We need more made in Europe success stories funded from seed to exit, that then list on the DAX, FTSE or CAC.

Relaxing competition rules to enable market consolidation in sectors such as telecoms. This is mainly about delivering higher rates of investment in connectivity and profiting from returns to scale. I, for one, can vouch for how crap mobile internet is across Europe, and have often moan about how many productive hours of work must be lost each year by people on trains.

A new trade agenda to increase the EU’s economic independence, that to quote the report “coordinates preferential trade agreements and direct investment with resource-rich nations, the building up of stockpiles in selected critical areas, and the creation of industrial partnerships to secure the supply chain of key technologies”. Nuff said.

Greater use of joint procurement in the defence sector, to improve interoperability (I for one learnt that there are currently 12 different types of battle tanks operated in the EU), and standardisation of equipment, and to buy from European suppliers, to help these companies to scale. The arresting statistic here is that “between 2022-2023, 78% of total procurement spending went to non-EU suppliers, out of which 63% went to the US”.

However, none of this will happen without simpler and faster decision making between member states. Draghi calls for a "Competitiveness Coordination Framework" to better align and speed up decision-making processes that are typically taken issue by issue, with multiple vetoes along the way. Anyone who knows anything about European super parliamentary bureaucracy knows that this will be a tall order, but in the spirit of the report, let’s believe that impossible is nothing.

“The reasons for a unified response have never been so compelling — and in our unity we will find the strength to reform.”

And what about a former EU member, the UK?

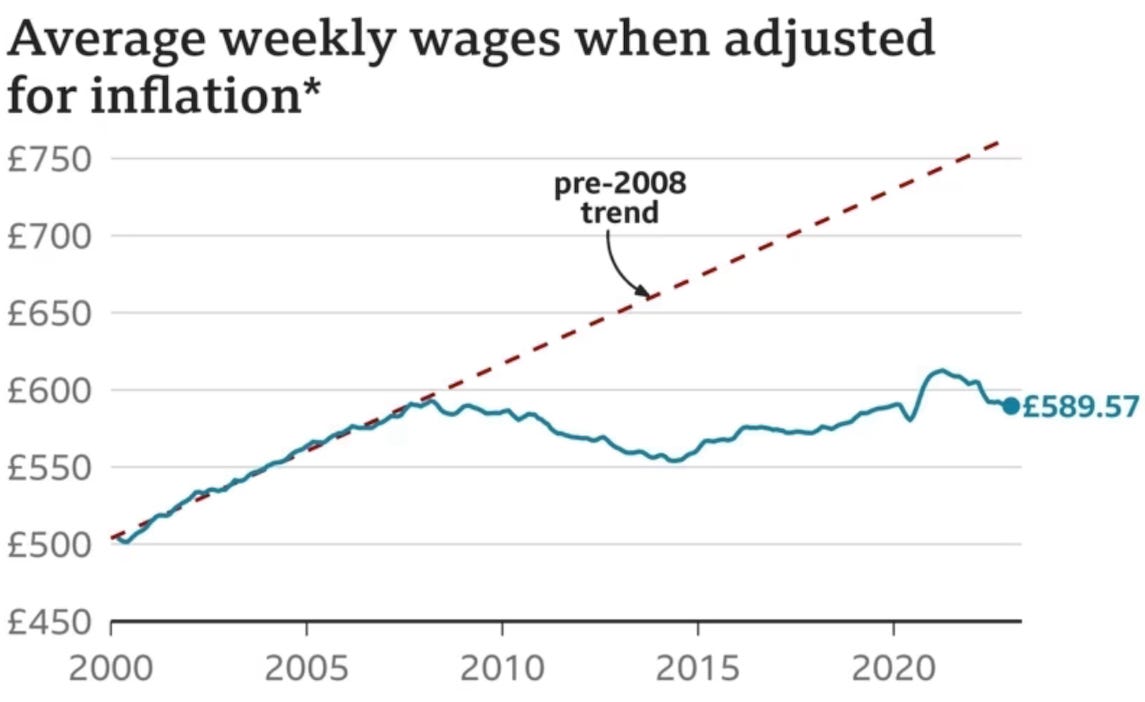

“Poorer than Poland by 2030” ran a number of headlines at the end of last year, based on forecast growth data, which suggested the average Briton would be worse off than the average Pole if UK real wages continued to flatline. In real terms, the average Briton is no better off today than they were in 2007. That’s 17 years of things not getting better. Just let that fact sink in for a minute.

The Guardian's John Harris, who I consider to be the best "mood of the nation" reporter writing today, sums it up perfectly in a recent piece that reflects upon the lack of hope or positive vision being projected by Britain's new Labour government:

“Among all the numbers, there is a huge story here about the everyday reality of people’s lives. What I would call ambient austerity – litter everywhere, overgrown grass verges, potholed roads, rusty slides and swings – is now deeply ingrained [...] Britons are knackered and despondent, for very obvious reasons bound up with a phase of history that began with the financial crash of 2008 and everything it triggered, only to lead on to the convulsions of Brexit, the pandemic and a cost of living crisis that millions are still coping with”.

As a Londoner who has relocated to Munich, I sense what Harris says whenever I am back in the UK, especially in regions outside of affluent London. People and places simply look tired and fed up.

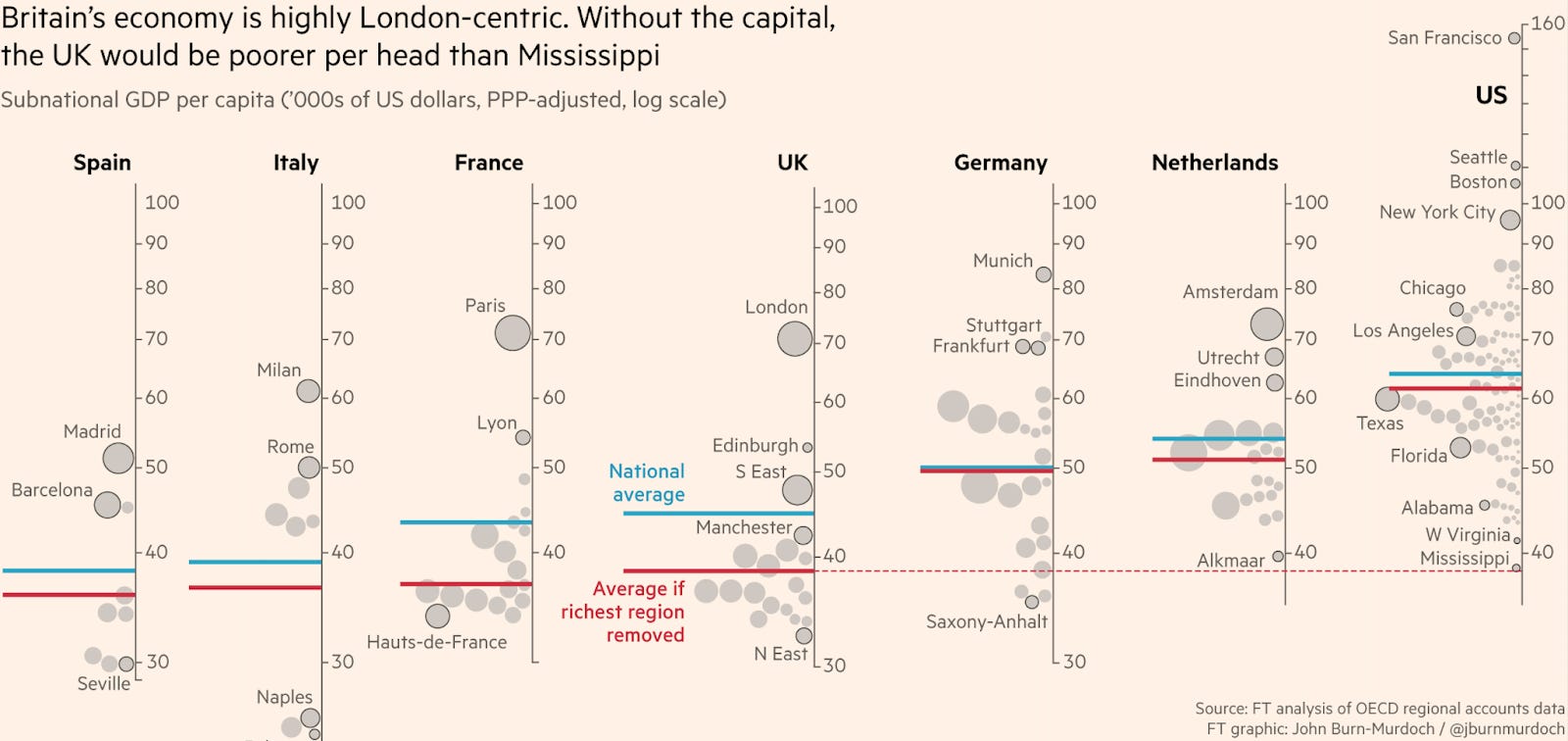

National averages disguise stark regional inequalities

Britain is fast becoming a poor country with a rich region. The same is true of France. The gap between the blue and red horizontal bars in the graph below shows the extent to which a country is dependent on a single dominant economic centre. Germany is more equally distributed than France and UK, but it still has pockets like Munich’s cashmere bubble where the average inhabitant is 60% better off than the average German. Many Europeans are now worse off than the Mississippians, and a long way from the wealthy Americans who live on the East and West coasts.

Growing the pie and sharing the pie are not the same

We have talked a lot about galvanising growth, but very little about how this growth is apportioned, and who reaps its rewards. Draghi’s report makes sure to point out that Europe is more equal, in gini coefficient terms, than other global regions, but his focus is on first growing the pie before talking about who gets what share. As we have established, Americans are more economically productive, and now significantly richer in dollar terms than most Europeans, but I don’t know many people living on the “old continent” who look across the Atlantic in envy at their quality of life, the plasticity of their culture nor the rough justice metered out by an unerring belief in the American dream. Take a walk through San Fran, the wealthiest metropolitan area on the planet, and you see cyber trucks driving past smack addicts openly defecating on the streets.

This should be dystopian science fiction, not the richest country on earth.

Which is to say, none of what Draghi’s report recommends is worth it if it doesn’t amount to equitable growth distributed among more than a handful of already dominant economic centres. I just hope that revitalising a continent that has lost much of its dynamism - in a way that is true to European social, ethical and political principles - will not prove to be a paradox.

It is weird how reality has caught up with forecasts and warnings from 20 years ago. I left Germany (and Europe) in 2016 for the US to pursue my ambitions there and it has been a great decision for me and my family. I left because I saw the stagnation happen in Germany in the early 2010s and I didn't want to stick around to be hit with the bill for it later. I wanted to build wealth for myself and my family - not be taxed into oblivion for wrong spending decisions the German state made year after year.

It looks like I was 1000% correct with my assessment of Germany's and Europe's future in the 2010s.